[From Wilderness Magazine, 2011-2012. Click here to see the full issue in pdf format. Click here to learn more about the Bodie Hills Conservation Alliance.]

[From Wilderness Magazine, 2011-2012. Click here to see the full issue in pdf format. Click here to learn more about the Bodie Hills Conservation Alliance.]

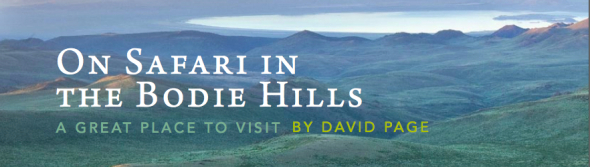

THE INFAMOUS WILD WEST TOWN SITE—since 1962 preserved in a state of "arrested decay"—was at its fit-for-the-big-screen best, with cumulous clouds over the western ridges and great sidelong shafts of late-afternoon sun on antique timbers and spring-green hills. Even at five minutes to closing, the parking lot overflowed with dusty RV's and rental cars. But less than a mile down-canyon, along the trickle of Bodie Creek, what was once the main (and notoriously bandit-infested) stage road to Aurora turned rutted and wild—and empty.

At the edge of a meadow thick with wild daisies, before the Nevada state line, we turned onto a lonely, two-track Jeep trail. I locked the hubs and shifted into 4-wheel-drive.

Up we climbed into the heart of the Bodie Wilderness Study Area (WSA), one of three such designated areas surrounding the state historic park that together make up nearly half of the Bureau of Land Management's 200,000-acre Bodie Hills Complex. Because of the primeval nature of the landscape, the exceptional biodiversity, the critical water sources and habitat (including for threatened species like the greater sage grouse and the Lahontan cutthroat trout), the possibilities for solitude, the outstanding geological, cultural, and scenic value of these areas, they were inventoried by the BLM back in 1979 as having potential for wilderness designation.

Since then, the BLM has had to toe a delicate line while waiting for Congress to decide whether to protect these areas or release them so they can be developed. On the one hand, the agency is required to honor historical activities such as mining (with valid claims) and off-road vehicle use (on existing roads and trails). On the other hand, by law, it must manage the areas "in a manner so as not to impair [their] suitability for preservation for wilderness."

Photo by John DittliWe pitched our camp with some friends at an old fire ring at the edge of Dry Lake, at about 8,000 feet, on a high plateau. A band of pronghorn frolicked beside the cows on the stubble grass playa. To the east rose the Beauty Peak cinder cone; to the west the twin summits of Bodie Mountain and Potato Peak, dark colonies of willow and quaking aspen clustered in their folds.

Photo by John DittliWe pitched our camp with some friends at an old fire ring at the edge of Dry Lake, at about 8,000 feet, on a high plateau. A band of pronghorn frolicked beside the cows on the stubble grass playa. To the east rose the Beauty Peak cinder cone; to the west the twin summits of Bodie Mountain and Potato Peak, dark colonies of willow and quaking aspen clustered in their folds.

With the day's last light fading over the snow-dappled Sweetwater Range, the boys watched their first satellite run across the sky. A barn owl hovered for a minute or two over our little campfire as if to study marshmallow roasting techniques. Later, when the boys were zipped into their bags, the coyotes—dozens of them, it seemed—began a round of yipping and shrieking out in the darkness, all around us. The next morning, along the edges of the basalt flows, we came upon ancient petroglyphs and chippings of obsidian. We found bleached cow bones, pincushion phlox, pennyroyal, waist-high thickets of red columbines, and Basque sheepherder inscriptions dating back to 1913.

Photo by John Dittli"You can see them sitting here," said our friend John Dittli, a photographer, noting how radically the outside world had changed in a century. This place, by contrast, was still essentially the same as when the first people came though 10,000 years ago.

Photo by John Dittli"You can see them sitting here," said our friend John Dittli, a photographer, noting how radically the outside world had changed in a century. This place, by contrast, was still essentially the same as when the first people came though 10,000 years ago.

In the afternoon we made our way back through Bodie. Our vehicles climbed up along the flanks of Potato Peak to the headwaters of Rough Creek—one of two streams in the Bodie Hills determined by the BLM to be eligible for federal Wild and Scenic River status. We splashed in the cool, clear water, walked barefoot in the grass, strolled through fields of wild iris and onion to drink from the springs. Then, before heading down Aurora Canyon, back to civilization and pizza at the Virginia Creek Settlement, we stopped off to explore the abandoned Paramount mercury mine.

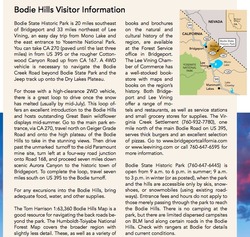

Click image for visitor infoThe Paramount site, its fifty-year-old mine works and tailings piles now in the early stages of reclamation by wild aspen groves, "is rated as having a high potential for occurrence of gold, silver and mercury," according to a recent BLM report, and is of great interest to Electrum, a gold mining company that already has begun exploration. “Developing a gold mine here,” says The Wilderness Society’s Sally Miller, “would cut out the ecological heart of the Bodie Hills. Mining would pollute the water, harm wildlife, and forever scar the landscape."

Click image for visitor infoThe Paramount site, its fifty-year-old mine works and tailings piles now in the early stages of reclamation by wild aspen groves, "is rated as having a high potential for occurrence of gold, silver and mercury," according to a recent BLM report, and is of great interest to Electrum, a gold mining company that already has begun exploration. “Developing a gold mine here,” says The Wilderness Society’s Sally Miller, “would cut out the ecological heart of the Bodie Hills. Mining would pollute the water, harm wildlife, and forever scar the landscape."

To secure permanent protection for this special place, The Wilderness Society, Friends of the Inyo and other organizations formed the Bodie Hills Conservation Partnership. “We are developing a plan with other stakeholders to protect the area’s outstanding natural and cultural values, enhance recreational opportunities, and help boost the local economy,” Miller explains.

With Congress now considering legislation (H.R. 1581) to drop protection of all remaining WSA's across the country, including in the Bodie Hills, the future of this unique landscape is far from certain.